This article first appeared in the Jul/Aug 2014 issue of World Gaming magazine.

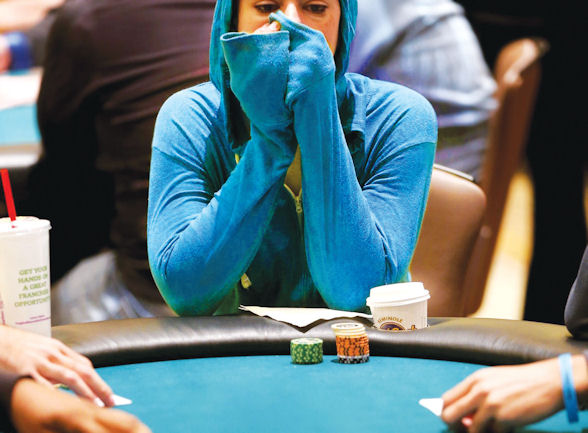

Even the most talented young players quickly learn one inevitable truth about tournament poker – it can be an incredibly expensive way to make a dollar! Fortunately, for those whose bank accounts are yet to catch up to their potential, there is another option … staking. WGM takes an in-depth look at how staking works and what can be reasonably expected from both players and their backers alike.

Tournament poker is a tough gig to get into. As alluring as those multi-million dollar prize pools at major tournament series such as the WSOP, APPT and Aussie Millions can be, the old saying “it takes money to make money” rings truer in poker than just about any other pastime. With buy-ins typically ranging anywhere from US$1,100 to US$10,000 and above, it can get very expensive, very quickly for players going through a tough run.

And while we all dream of that first big poker payday, the fact is that most players don’t have millions of dollars sitting around in their bank accounts.

So how do these players find the funds to keep entering big events? The answer is staking – an arrangement between a player and a backer whereby the backer provides either some or all of the buy-in in return for a percentage of any winnings the player comes away with.

The details of staking arrangements can vary significantly. A player might seek out a one-off deal with a backer in order to take a shot at a big buy-in tournament he could never normally afford to enter, or he might be on a long term deal whereby the backer pays for multiple entry fees or even provides the player with a full bankroll.

But whatever the details of each individual deal, there remain a few constants when it comes to staking.

The most obvious of these is that not everyone can get a staking deal. The fact that you’ve always wanted to play the WSOP Main Event doesn’t mean someone is just going to give you US$10,000 to fulfil your dream. Backers are basically investors, so although they might be taking a risk by staking a player they are doing so with a decent expectation that their investment will pay dividends in the long run.

As a result, professional backers are very careful about who they choose to stake. Any player that comes onto the backer’s radar will generally need to show that they are a winning player or that they possess skills at the table over and above the abilities of the vast majority. After all, it’s not just the player losing money if the results don’t come.

Another common aspect of staking is what is known as “makeup”. This is basically an insurance policy for the backer and refers to whether or not a player is required to pay back their backer for some or all of the buy-ins the backer has contributed for tournaments where the player failed to cash. For example, in a deal with full make-up, a player who was staked into and busted early from a US$10,000 tournament would have to repay their backer that US$10,000 at a future time. If they were to cash for more than US$10,000 in their next tournament, that US$10,000 owing would be paid to the backer before any profits were split.

Although reducing risk is at the heart of makeup, it also serves a second important purpose in that it ensures the player is just as invested in their results as the backer. Without makeup, players would basically be playing for free with no ramifications should they fail to make profit – the inference being that players are far more likely to bring their “A” game when they’re not just playing with someone else’s money.

Staking without makeup was much more common a decade ago and deals usually saw the backer take a higher percentage of the profits, but in most cases today backers are happy to lower their cut due to the reduced risk that makeup provides.

With makeup and a share of any profits, this all sounds like it’s a great deal for the backer provided those they stake are winning players, but players possess a bargaining chip of their own – “markup”. Not to be confused with the similar sounding “makeup” already explained, markup refers to the added value a player places on themselves – or the edge they believe they have over the rest of the field as a whole – which they will then charge their backer for.

This means that in some cases, particularly when a player sells a number of “shares” in themselves for an upcoming tournament, the total cost to those who buy the shares (their backers) is actually more than the buy-in. Much like a defendant paying more to hire the best lawyer in town rather than risk a cheaper and less effective option, markup is a good player charging more for their expertise and ability.

Of course, if a player is going to charge markup it is important that the amount is fair and equitable which is why it is very difficult for players to justify doing so without a proven track record over time.

Markup might, for example, be charged as follows: a winning player has established a lifetime ROI (Return on Investment) of 15 percent and understandably has no trouble finding people ready to stake him for upcoming tournaments. He decides to sell 50 percent of his action in the US$10,000 WSOP Main Event, which equates to US$5,000 worth, but does so in five increments, or shares.

Usually each share would therefore cost US$1,000 but the player also wants to leverage his edge. Given his ROI of 15 percent, he decides that charging an extra 10 percent for each share is reasonable given that it still comes in well under that 15 percent. So each share would be advertised as being with a markup of 1.1 and would cost US$1,100. This US$1,100 represents exactly 11 percent of the buy-in but the backer will only receive 10 percent of the profit should the player cash.

Again, just as it is important that players adding a markup don’t charge more than their ability is worth, it is also vital for those buying the shares to take a close look at how much of their action the player is selling.

Because this method of selling multiple shares tends not to involve “makeup” – the player doesn’t need to pay these backers back – they could conceivably sell 100 percent of themselves and with markup guarantee themselves a profit even if they bust early. In other words, a player who sells 100 percent of themselves stands to win nothing if they make the money so there is no financial incentive for them to play their best or to value their tournament life. In the example above, whether they bust first hand or win the whole thing, the player pockets exactly US$500 – no prizes for guessing the best option!

Although staking provides a unique opportunity for players to play tournaments they would otherwise be unable to afford, it is also a serious business and while there was a time when deals were made with the shake of a hand, these days they come with detailed contracts between the player and backer. Due to the level of trust involved, it also wise to enter into these sorts of deals only with people you know reasonably well, and of course keeping accurate records goes without saying.

Nevertheless, staking plays a huge role in the poker industry as a whole and it’s fair to say the game wouldn’t have enjoyed the incredible growth it has sustained over the past 10 years or so without it. Who knows how many more doorways it will open in the future?